Great Design Thinking |

24/02/19

I have recently been researching Rem Koolhaas for a presentation. Known for his striking structures, he has built a reputation as one of the top architects of the 21st century. The more I found, the more I apricated both their beauty, and the incredible engineering required to create such (often gravity defying) structures. As I delved into his many works I started to consider that it wasn’t necessarily the built structures that make his projects great, but the thinking behind them. Koolhaas has significant portfolio of conceptual, unbuilt designs – can they too be considered great? Can something be deemed great design if it is never built and experienced?

|

|

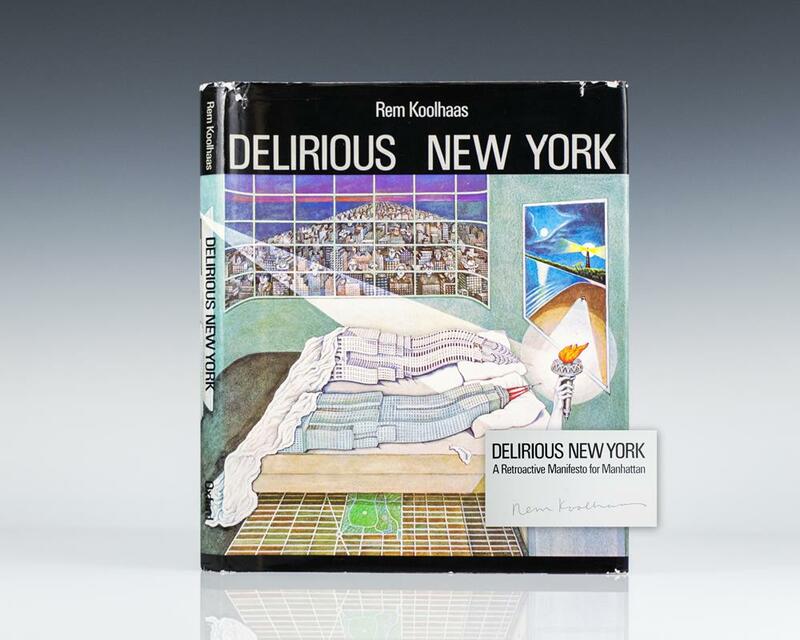

I could be argued that Rem Koolhaas’ reputation is mostly built on proposals that have never come to fruition. He would never have articles titled ‘Worlds Most Controversial Architect’ written about him without ideas such as running tracks in skyscrapers, or the inclusion of hospital units for the homeless in Seattle Library. He has a habit of shaking up established conventions. He questions the ‘form follows function’ mantra of modernism in Delirious New York - his analysis of high-rise architecture in Manhattan. An early design method derived from such thinking was "cross-programming", introducing unexpected functions in room programmes.

|

|

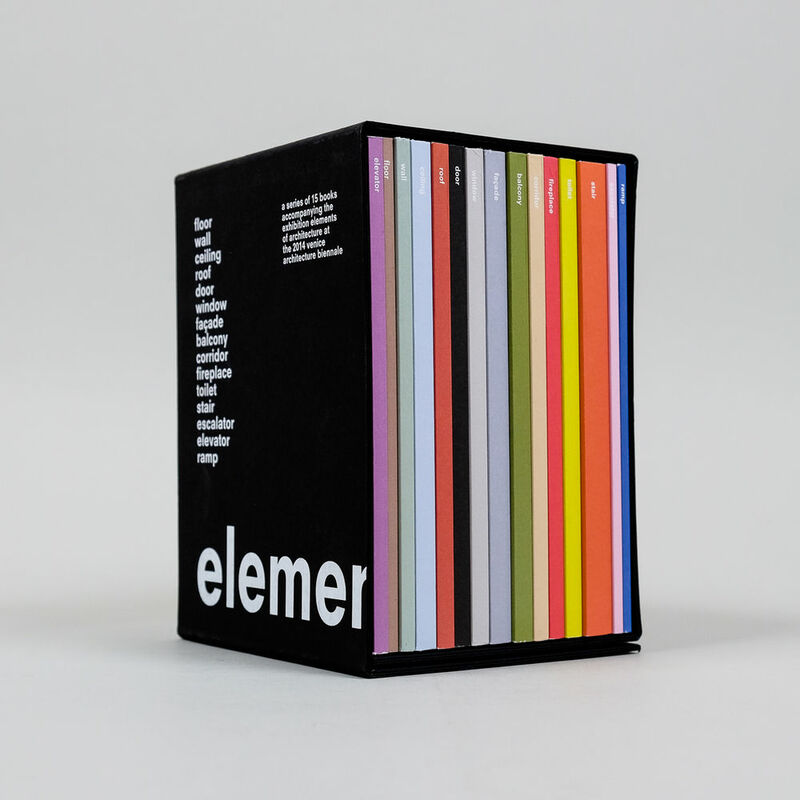

Or perhaps it’s his books that are truly great. His most biggest contribution to the cultural landscape is as an urban thinker. Koolhaas has been writing provocatively and incisively about cities for decades. His writing celebrated the “culture of congestion” and the creative potential of vertical cities, whilst everyone else was viewing a New York City that had lost its appeal. It was seedy, grotty and decayed; people were increasingly lonely and isolated in the crowds. When cultural figures were condemning the “mall-ification” of the world’s cities in 2000, Koolhaas published The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (written with his students), a paean to shopping as “the last remaining form of public activity”. When everyone was looking to Copenhagen as the exemplar of civilised city living, Koolhaas was studying the chaotic inventiveness of Lagos, which he suggested was the actual (rather than the ideal) model for cities of the future.

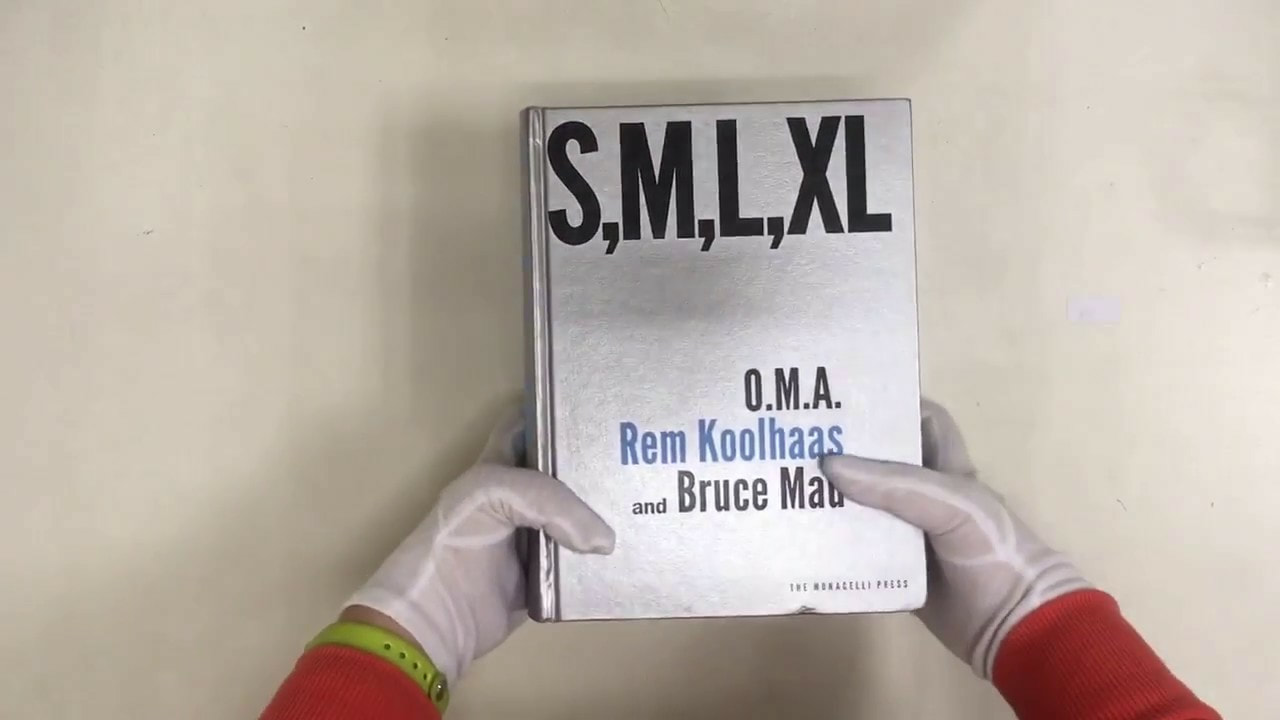

He sees opportunity in what others regard as urban debris. His ideal city is a place that is “all things to all people.” Built WorkIn 1975 he founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, or OMA, along with fellow architects Elia Zenghelis, Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesendorp. Among the firm’s early projects were the Almere-Haven police station and the Netherlands Dance Theater in the Hague. In 1995 Koolhaas published S,M,L,XL, a collaboration with graphic designer Bruce Mau, which celebrated the firm’s previous work. Over the past ten years, Koolhaas has unveiled some of his most innovative creations, including the CCTV Center in Beijing, the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in China.

The Seattle Library is perhaps my favourite of his built works. It completely reinvents the library - no longer a space dedicated to the book. It recognises mass digitisation, but not as an argument for the obsolescence of libraries. Rather the space is adapted to the modern day; all potent forms of media – new and old – are presented equally and legibly. In line with his early 'cross-programming ' philosophy Koolhaas created a flexible civic space. It is this success at blurring the lines between a thriving social gathering place and an adaptable store for information that makes the design so great. |

Unbuilt WorkKoolhaas and OMA are perhaps best known for the spectacular and controversial CCTV Headquarters in Beijing and their dramatic plans for cities in the Middle East and Asia. But I think some of Koolhaas’s best high-rise designs, and often his most subversive, are much simpler and have largely remained unbuilt. They’re witty and architecturally striking without being abrasive. Koolhaas has a genuine affection for the classic commercial high-rise. He sees it as a product of our cultural and political environment. Though these buildings appear complex their core idea is often quite simple: a basic formal manipulation of a common building type. Koolhaas’s ideas can be broken down into simple, architectural moves: shift tower, twist tower, step tower and so on. But simplicity is hard. They illustrate an expert’s familiarity with commercial building types and the history of the city. To break the rules, as it is said, you first have to know them. And Koolhaas knows them well. Whether or not they are built, his buildings represent a search for newer modes of living.

|

Sources:

https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/rem-koolhaas-buildings-article

https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/why-rem-koolhaas-worlds-most-controversial-architect

https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/talking-with-rem-koolhaas-the-architect-behind-the-central-library/

https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/rem-koolhaas-buildings-article

https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/why-rem-koolhaas-worlds-most-controversial-architect

https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/talking-with-rem-koolhaas-the-architect-behind-the-central-library/